【紀念西西】西西英譯者Jennifer Feeley:翻譯西西使我變成一個更有想像力的思想家和作家,通過翻譯她而累積的知識是驚人的

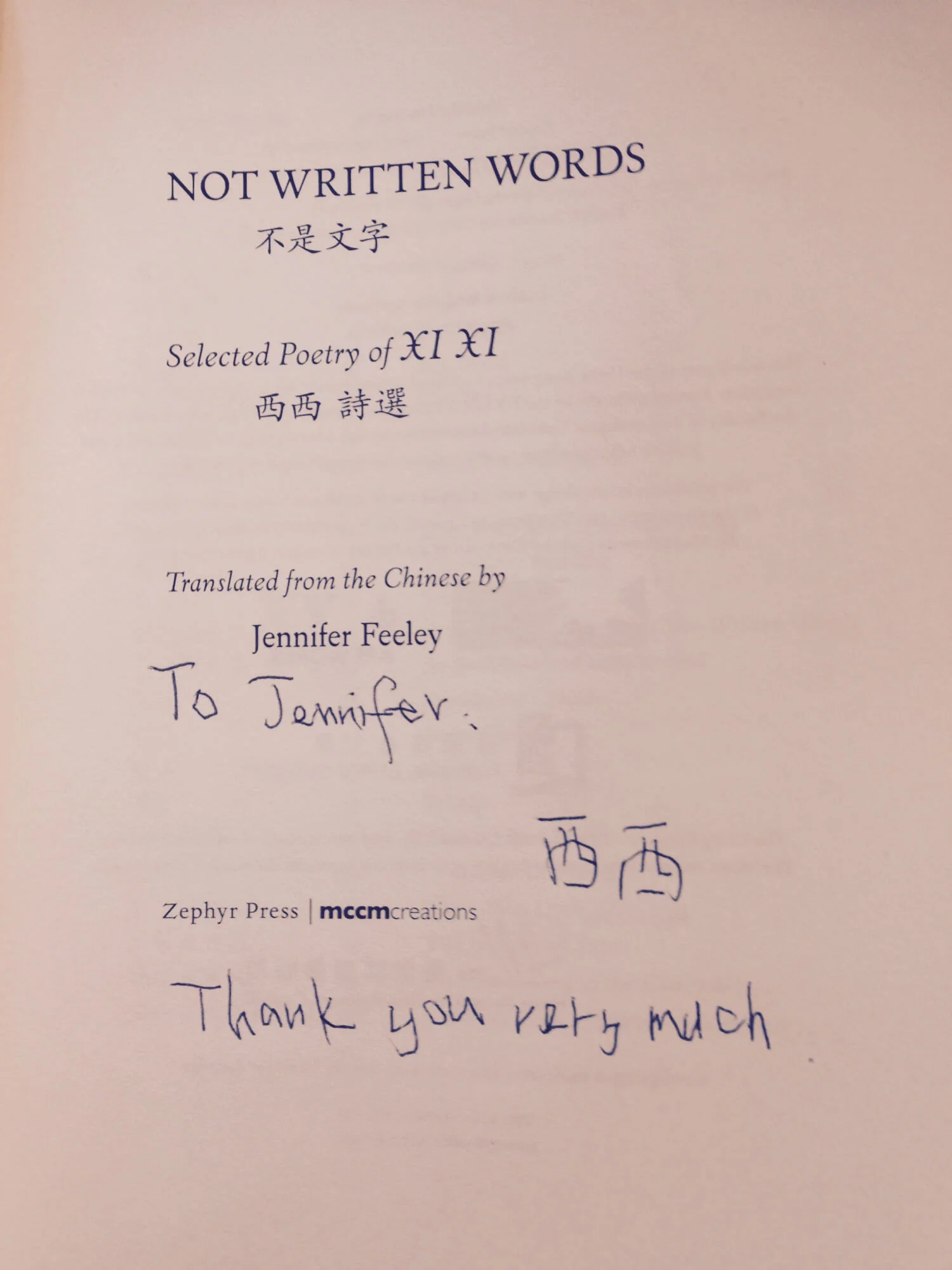

(編按:西西的文學成就及影響力,跨地域跨文化,曾先後獲美國紐曼華語文學獎(2019 Newman Prize for Chinese Literature)及瑞典蟬文學獎(Cikada Prize 2019)。二○一六年出版的西西詩選英譯《Not Written Words 不是文字》,譯者Jennifer Feeley(費正華)藉此書獲得Lucien Stryk亞洲文藝翻譯大獎,她翻譯的西西小說《哀悼乳房》也將出版。她為本刊撰寫紀念文章,憶述跟西西交往的經過,及翻譯西西作品的得着。原文為英文,由本刊翻譯為中文。)

〈像我這樣的一個譯者〉費正華

像我這樣的一個譯者,是很幸運可以遇上像西西這樣的一個作者,教曉我文學翻譯如何可以是雙向的友情交流。當我哀悼她的逝世,通過閱讀和翻譯她的作品,我得以繼續我們的談話並得到安慰,我感激她留下超卓的文學遺產,也很榮幸可把她的文字翻譯成英語。我亦從她給我的其他禮物中得到慰藉,因着它們背後的意味和故事而對我非常珍貴。

二○一九年三月,西西第一次來到美國,接受奧克拉荷馬大學頒發的紐曼華語文學獎。作為她的詩歌主要英譯者,我受邀出席典禮。當我們第一晚在住宿旅館的公共空間聚會,西西給每人送上禮物。她遞給我一個小布袋,我一眼就認出來,那是來自我喜歡的香港小店Mushroom。

你怎麼知道這是我喜歡的店?我問。

她笑着說,這也是她喜歡的店,更確切來說,這是她喜歡的分店(香港有幾家店),在旺角的朗豪坊。

那也是我的愛店!我說。

每次在香港,我也會到這家分店去,通常只是欣賞一下那些精品。她怎會知道呢?我從來沒有跟她提過,而根據我的記憶,她應該也從沒看見我拿着那裡的東西。驚訝於我們喜歡同一家商店,我輕輕把袋裡的東西倒出來,是一對可愛的鼠尾草綠魚耳環。這是一份吉祥的禮物,因為魚在中國文化中寓意繁榮和豐盛,但更重要的是,它們是我會為自己挑選的禮物。西西知道我的品味讓我很驚喜,而當然我得戴上它們參加兩天後的紐曼獎頒獎典禮。

然後,秘密暴露了:Mushroom是通向我心的路。我的好朋友楊維也是西西的超級粉絲,那年夏天她路過香港,就在銅鑼灣的Mushroom分店給我買了一份生日禮物。那年九月,當我打開她寄給我的包裹時,我高興得尖叫起來,發現那個熟悉的布袋,上面有一隻虎紋貓站在一罐草莓醬上。我抖出裡面的東西:一只精緻的金鍊裝飾着淡藍色珠子,一輪淡黃色新月在中央,上面一隻藍色大眼睛正盯着我,一顆小金星從月亮鉤子垂下來。

啊,你從西西那裡學來的!我告訴她。

西西送贈的禮物 沒有約定的巧思

兩個月後,二○一九年十一月我在香港,在序言書室參加致敬西西詩歌的活動,也出席香港國際詩歌之夜。旅程頭幾天,我住在香港理工大學對面的酒店唯港薈,剛好是示威者與警察對峙的位置。那時我剛從斷腳的傷患康復過來,所以對於催淚彈煙霧中走動分外謹慎。因此,我在城中第一天,西西和何福仁來看我,他們擔心我的腿,還有我的酒店跟事件距離很近。我們相約在酒店喝下午茶。本來,我戴了那年夏天在威尼斯買的藍綠色玻璃手鍊,猜想西西會喜歡這鮮豔的顏色,而且它和我的衣服十分搭配。打算離開房間時,卻發現我那月亮手鍊上的藍眼睛正盯着我,我就決定換掉手鍊,心想西西會喜歡這可愛的月臉。

西西才跟我打完招呼,就瞄到我的手腕,她瞪大了眼睛。突然,她開始手舞足蹈,興高采烈地談論耳環。

這是Mushroom的,我說,指着手鍊。你給我買魚耳環的那個地方。

不是魚耳環,她用英語堅持,搖了搖頭。星星和月亮。

星星和月亮?不,她在奧克拉荷馬確實送給我魚耳環。我們走到酒店大堂的咖啡店時,她仍繼續不停談論耳環。她為什麼這樣興奮?我們甫坐下,她就急不及待交換禮物,並把一個牛皮紙袋放在我面前。我掏出一條繡有泰迪熊的海軍藍Polo圍巾,馬上想起在西西的書《縫熊志》中揚名的手縫熊。然而,並不是圍巾讓她如此興奮。紙袋的底層,有我們最喜歡的商店那個熟悉的小布包,甚至還沒打開,我就已知道了。

一對耳環,一隻是淡黃色新月,上面一隻巨大的藍眼睛仰望着我,另一隻是淡黃色星星,有兩隻巨大的藍眼睛。懸垂的星星和月亮耳環,跟維在我的生日送的月亮手鍊完美搭配。我吸一口氣。維和西西不認識對方,我也不曾在社交媒體上分享過這月亮手鍊。西西根本不會知道我有一只跟那對耳環完全搭配的手鍊。就當是命運或機遇吧,但我無法遏止驚歎,我生命中兩個重要的人物,如何在不知情底下各自給我送上我最喜歡的商店的一套搭配飾物。

那天晚上,我一邊欣賞那雙新的星月耳環,一邊深思我和西西的美學品味多麼相近。我喜歡Mushroom店裡那些異想天開、童話風格的珠寶和配飾,是因為我在翻譯西西過程中滋生了對奇思妙想和童話的喜愛嗎?或是,我最初受吸引去翻譯西西的作品,是因為我們都天生就喜歡奇想和童話故事?

西西重視翻譯 撰詩向譯者致敬

不管怎樣,西西給我足夠的關注,還找來令我快樂的東西,這讓我很感動,而我們對所有奇想物事的共感,只是把我們相投的志趣連繫起來的眾多線索之一。一般來說,譯者常會沉浸在他們翻譯的作家的世界中,盡可能了解某個作者的生活和作品。我花了那麼多時間去了解西西和她的寫作,但我可沒有停下來去意會原來她也在了解我。我從沒有想過作者也想要了解他們的譯者,但是,西西卻關注到那些常被忽略的事情。她在紐曼獎的領獎致辭中,甚至寫了一首讚美文學翻譯家的詩。

〈向傳譯者致敬〉西西

在書店中遇上一位年青朋友

朝我走來,問我買書時選擇原著

還是譯本?譯本,他強調

充滿謬誤、錯解、增删

他堅持讀外語作品

必須親炙原文

以免受騙

對呵,但願我也擁有巴別塔

每一個房子的鎖匙

看不同的布置

賞玩每一樣藏品

聆聽每一種獨特的聲音

那是血和汗結的果

可是我已經不再年輕了

朋友,要不是有人引導

用我懂得的言語

又有什麼法子

認識彼此?

有些什麼,如果在轉譯時失去了

可有些,卻是增益哩

費神盡力,為了達成同一目標

換一副面目出現

也是挑戰

詩的旅程從沒有完成

要被閱讀,並且接受誤讀

要重新探險

去到遙遠的地方

愈遠愈好

即使全能的上帝

也要借助天使

我認識的天使,向我走來

他們不是能鳴的鑼 ,會響的鈸

他們各有個性

他們有愛

西西愛語言實驗 譯者的歷險與收穫

翻譯西西作品的眾多收穫之一,是發現她確實寫了不少關於翻譯的文字,想到西西自己也是一個譯者,這也不足為奇了。在我目前翻譯的《哀悼乳房》中(即將由《紐約書評》出版,2024 年),她多次討論翻譯,例如在等候醫療程序時分析《包法利夫人》不同譯本的字體和標點符號,或在醫院等候電療時,思考一個墨西哥短篇小說裡的西班牙文Sister一字,譯成中文該是「姐姐」還是「妹妹」,觀察到中文可以區分但西班牙文和英文沒有。整本書中,翻譯作為解讀文本化病體的隱喻,敘事者得出結論,沒有唯一而絕對的譯本。作為一個翻譯西西的文學譯者,可感受到被看見、被理解和被欣賞,而且常常感覺到我和她正在為我演出的一幕熱烈交談。

翻譯西西的作品時,很難不去思考翻譯的藝術,因為她喜歡用語言實驗,有些作品看來如此「不可譯」。每當我遇上她精妙的文字遊戲,我也面對同樣挑戰,要用英語重新創造類似遊戲。翻譯這些作品,把我從思考語言的傳統方式解放出來,邀請我去冒險和從中得到樂趣。也許這是為什麼這些「不可譯」的作品是我最愛翻譯的。舉例,在她的詩作〈一郎〉,她把日文漢字和句法與標準的書面中文融合,同時押韻(為了達到最大的韻律,原詩應以日文和普通話混合閱讀),或她的具象詩〈綠草叢中一斑斕老虎〉,詩題中的老虎隱藏於各種動植物的字詞中,不是由「王」字的意思顯示而是其象形特質,像老虎的斑紋。這些作品看來不可能翻譯,但其實是最令人愉快的,因為它們把我從舒適圈中拉出來,鼓勵我突破英語的界限,就像西西對中文所做的。

翻譯西西使我變成一個更有想像力的思想家和作家,我透過翻譯她而累積的知識是驚人的。我翻譯她的作品時,掉進數之不清的兔子洞,認識到粒線體夏娃、無花果樹如何繁殖、菲林拼接、水母和蛞蝓之間的共生關係、十八世紀法國伯爵區分人類和怪物的分類系統……翻譯她的寫作需要閱讀(有時還要翻譯)卡爾維諾( Italo Calvino)、葛拉斯(Günter Grass)、托馬斯曼(Thomas Mann)、班雅明(Walter Benjamin)、福樓拜(Gustav Flaubert),還有中國古典詩歌和散文,或者觀看黑澤明、愛森斯坦、高達、卓別靈的電影,在西西引領下欣賞這些作品。她的小說、散文和詩歌,幾乎每一段或每一節都帶來意料之外但豐饒的繞路。

當我結束翻譯《哀悼乳房》,我細看堆放在桌邊她的其他作品,想着不知道接下來她會帶給我什麼樣的歷險,我們未來會有什麼談話。她手造的兩隻布熊:嵇康和阮咸,守護着這些書。去年夏天,我的母親猝然逝世。西西和何福仁給我送來這兩位朋友,讓我在哀痛中得着安慰與守護。一年半以後,當我哀悼它們的創造者離世,它們再次安慰和守護我。它們讓人憶起那個把它們縫接起來的人,其幽默、溫柔、溫暖和慈悲,以及像我這樣的一個譯者,何其有幸可稱她為朋友。

原文為英文,中譯:Chan Ning

(編按:文中小題為本刊編輯所加)

<A Translator Like Me > by Jennifer Feeley

A translator like me is fortunate to have found an author like Xi Xi who has taught me how literary translation is an exchange of friendship that extends both ways. As I mourn her recent passing, I find comfort in continuing our conversations through reading and translating her work, grateful for the extraordinary literary legacy she has left behind, and honored to be entrusted with the gift of bringing her words into English. I also find comfort in other gifts I’ve received from her, objects that are invaluable to me because of the intentions and stories behind them.

In March 2019, Xi Xi came to the US for the first time to be awarded the Newman Prize for Chinese Literature (Poetry) at the University of Oklahoma. As the primary translator of her poetry into English, I was invited to join the celebration. While we gathered in the common area of our bed and breakfast that first evening, Xi Xi distributed gifts to everyone. She handed me a small cloth bag that I immediately recognized as being from my favorite Hong Kong boutique, Mushroom.

How’d you know this is my favorite store? I asked.

Smiling, she told me it was also her favorite, and to be precise, her favorite branch (there are several in Hong Kong) was the one housed in Langham Place in Mong Kok.

That’s my favorite too! I said.

Every time I’m in Hong Kong, I visit this particular branch of this boutique, usually just admiring the merchandise. How did she know? I’d never mentioned it to her, and as far I could remember, she’d never seen me with anything from there. Stunned that we shared a favorite store, I gently poured the contents out of the bag, revealing a lovely pair of sage green fish earrings. An auspicious gift, as fish symbolize prosperity and abundance in Chinese culture, but even more than that, they were something I would’ve picked out for myself. I was amazed that Xi Xi knew my taste, and of course I had to wear them for the Newman Prize ceremony two days later.

After that, the secret was out: Mushroom was the way to my heart. My close friend Wei(楊維), who, like me, is a huge fan of Xi Xi’s, stopped by the Causeway Bay branch of Mushroom to buy a birthday gift for me when she was in Hong Kong that summer. That September, I squealed with delight when I opened the package she’d sent me, discovering that familiar cloth bag featuring a tabby cat standing atop a jar of strawberry jam. I shook out the contents: a delicate gold bracelet adorned with light blue beads, and in the center, a pale-yellow crescent moon with a giant blue eye staring up at me, a tiny gold star dangling from the moon’s hook.

Ahh, you learned from Xi Xi! I told her.

Two months later, in November 2019, I was in Hong Kong to participate in an event celebrating Xi Xi’s poetry at Hong Kong Reader Bookstore( 序言書室) and to attend International Poetry Nights (香港國際詩歌之夜). For the first few days of my trip, I stayed at the Hotel ICON, located across from Polytechnic University, where a stand-off between protestors and police happened to be taking place. I was also recovering from a broken leg, so I was cautious about venturing out amid the plumes of tear gas. As such, my first full day in the city, Xi Xi and Ho Fuk Yan came to check on me, concerned about my leg and also the proximity of my hotel to the events unfolding across the way. We met for afternoon tea in the lobby of the ICON. Initially, I’d put on a teal glass bracelet I’d bought in Venice that summer, thinking Xi Xi might appreciate the vibrant color, and it matched my dress perfectly. Just as I was about to leave my room, however, I spotted the bright blue eye of my moon bracelet peering up at me, and decided to switch bracelets, thinking Xi Xi would appreciate the cute moon face.

As soon as Xi Xi greeted me, she glanced at my wrist, her eyes widening. Suddenly, she began gesturing animatedly, babbling about earrings.

This is from Mushroom, I said, pointing at the bracelet. The same place where you got me the fish earrings.

Not fish earrings, she insisted in English, shaking her head. Star and moon.

Star and moon? No, she’d definitely given me fish earrings in Oklahoma. As we walked to the café in the lobby, she continued chattering about earrings. Why was she so excited? As soon as we sat down, she couldn’t wait to exchange gifts, and set a brown paper bag in front of me. I pulled out a navy Polo scarf embroidered with a teddy bear, immediately calling to mind Xi Xi’s handstitched bears made famous in her book The Teddy Bear Chronicles. It wasn’t the scarf that had her so excited, however. At the bottom of the bag was that familiar small cloth bag from our favorite shop. Even before I opened it, I knew.

A pair of earrings, one a pale-yellow crescent moon with a giant blue eye gazing up at me, the other a pale-yellow star with two giant blue eyes. Dangling star and moon earrings that perfectly matched the moon bracelet Wei had given me for my birthday. I gasped. Wei and Xi Xi didn’t know each other, and I hadn’t shared a picture of the moon bracelet on social media. Xi Xi had no way of knowing that I had the bracelet that matched those earrings exactly. Call it fate or serendipity, but I couldn’t stop marveling about how two important people in my life had each unknowingly given me part of a matching jewelry set from my favorite store.

That night, as I admired my new star and moon earrings, I reflected on how Xi Xi and I had similar aesthetic tastes. Did I love the whimsical, fairy-tale inspired jewelry and accessories in Mushroom because I’d developed a love of whimsy and fairy tales from translating Xi Xi? Or was I originally drawn to translating Xi Xi’s work because we both shared an innate love of whimsy and fairy tales?

Whatever it was, I was touched that Xi Xi paid enough attention to me to seek out things that would bring me joy, and our mutual affinity for all things whimsical was just one of many threads that connected us as kindred spirits. It is common for translators to immerse themselves in the worlds of the writers they translate, learning all they can about the life and work of a certain author. I’d spent so much time getting to know Xi Xi and her writing, but I hadn’t stopped to realize that she was also getting to know me. It had never occurred to me that an author might want to get to know their translator, but then, Xi Xi paid attention to that which was often-overlooked. In her acceptance speech for the Newman Prize, she even wrote a poem in praise of literary translators.

A Salute to Translators by XiXi

I see a young friend in a bookstore

he comes over, asks whether I buy books in the original language

or in translation. Translations, he accentuates

are rife with mistakes, misinterpretations, additions and deletions

He maintains that when reading foreign-language works

one must be well-acquainted with the original text

to avoid being led astray

Oh yes, if only I had a Tower of Babel

keys to every house

scoping out the various layouts

admiring each and every object

attuned to each unique sound—

the fruits of blood and sweat

But I’m not young anymore

friend, were it not for someone guiding me

in a language I can understand

how would we

know each other?

Some things are lost in translation

some, however, are gained

great pains taken to attain the same goal

the challenge of

taking stage with a changed face

a poem’s journey is never complete

it will be read and misread

explored again and again

traveling to far-off places

the farther off, the better

Even God almighty

must rely on angels

The angels I know walk toward me

they aren’t resounding gongs, or clanging cymbals

they each have distinct personalities

they have love[1]

One of the many rewarding aspects of translating Xi Xi’s work is how much she actually writes about translation, which perhaps is no surprise, considering Xi Xi was a translator herself. In her book that I am currently translating, Mourning a Breast (forthcoming from New York Review of Books, 2024), she discusses translation numerous times, such as analyzing the typeface and punctuation in various translations of Madame Bovary while waiting for a medical procedure to be performed, or while standing in line in the radiology department of a hospital, pondering whether the Spanish word for “sister” in a Mexican short story should be rendered into Chinese as “older sister” 姐姐or “younger sister” 妹妹, observing that Chinese makes distinctions that Spanish and English don’t. Throughout the book, translation serves as a metaphor for decoding the textualized sick body, with the narrator concluding that there is no sole, absolute version of a translation. To be a literary translator translating Xi Xi is to feel seen, understood, and appreciated, and often it feels like I am engaged in a spirited conversation with her about the very act I am in the midst of performing.

It’s also hard not to think about the art of translation when translating Xi Xi’s writing because of how “untranslatable” several of her works seem, given her fondness for experimenting with language. Whenever I encounter her clever wordplay, I am challenged to recreate something similar in English. Translating these pieces liberates me from conventional ways of thinking about language, inviting me to take risks and have fun. Perhaps this is why these “untranslatable” works are my favorite to translate. Take, for example, her poem “Ichirō” 〈一郎〉, which fuses Japanese kanji and syntax with standard written Chinese while playing with rhymes (and in order to achieve maximum rhyme, the original poem should be read in a mix of Japanese and Mandarin), or her concrete poem “A Striped Tiger in a Thicket of Green Grass” 〈綠草叢中一斑斕老虎〉 in which the tiger mentioned in the title is hidden among words for various flora and fauna, indicated not by the meaning of the character 王 but by its graphic qualities, which resemble the tiger’s stripes. Such works seem impossible to translate, but in fact are the most pleasurable, as they force me out of my comfort zone and encourage me to push the boundaries of English as Xi Xi does with Chinese.

Translating Xi Xi has made me a more imaginative thinker and writer, and the amount of knowledge I’ve accumulated from translating her is astonishing. I’ve tumbled down numerous rabbit holes while translating her work, learning about mitochondrial Eve, how fig trees reproduce, film splicing, the symbiotic relationship between jellyfish and slugs, an eighteenth-century French count’s classification system for distinguishing humans from monsters…Translating her writing has entailed reading (and sometimes translating) Italo Calvino, Günter Grass, Thomas Mann, Walter Benjamin, and Gustav Flaubert, along with classical Chinese poetry and prose, or watching films by Kurosawa, Eisenstein, Godard, and Chaplin, with Xi Xi guiding my appreciation of these works. Nearly every paragraph or stanza of her fiction, prose, and poetry brings unexpected but enriching detours.

As I finish translating Mourning a Breast, I study the stacks of other books she has written that are piled beside my desk, wondering what adventures she’ll bring me on next, what future conversations we’ll have. Two of her handmade teddy bears, Ji Kang(嵇康)and Ruan Xian(阮咸), preside over these books as guardians. After my mother unexpectedly passed away last summer, Xi Xi and Ho Fuk Yan entrusted me with these two friends to bring me comfort and watch over me as I mourned. A year and a half later, they again bring me comfort and watch over me as I now mourn the loss of their creator. They serve as reminders of the humor, gentleness, warmth, and compassion of the person who stitched them together, and how a translator like me is privileged to have been able to have called her a friend.

([1] English translation originally published in Xi Xi, “Newman Prize for Chinese Literature Acceptance Speech, 201,” translated by Jennifer Feeley, Chinese Literature Today 8.1 (2019): 12–13.)

PROFILE

費正華(Jennifer Feeley),耶魯大學東亞語言和文學所博士,曾翻譯多部作品,其中英譯西西詩選《Not Written Words 不是文字》曾獲得美國文學翻譯協會Lucien Stryk亞洲文藝翻譯大獎。其英譯的西西小說《哀悼乳房》將於2024年由《紐約書評》出版。